Whatever Happened to the Iraqi Kurds?

It has been nearly three years since the chemical bombardment of Halabja, a small town on Iraq’s northeastern border with Iran in which up to 5,000 civilians, mostly women and children, died a painful and well publicized death.

Despite the international outcry over this one infamous event, little was heard in the United States about Saddam Hussein’s brutal treatment of his own people until his invasion of Kuwait last August 2. Even now, virtually no mention is made of the many other times the Iraqi government has gassed its large Kurdish minority.

Halabja was not the first time Iraq had turned its chemical arsenal on the Kurds. Thousands — and most likely tens of thousands — of civilians were killed during chemical and conventional bombardments stretching from the spring of 1987 through the fall of 1988. The attacks were part of a long-standing campaign that destroyed almost every Kurdish village in Iraq — along with a centuries-old way of life — and displaced at least a million of the country’s estimated 3.5 million Kurdish population.

Since the outset of the Kuwait crisis, however, Halabja has become a leitmotif for Saddam Hussein’s disregard of human rights, and a major rationale for the war. Although chemical weapons were not seen in action in the latest Persian Gulf war, no one is disputing that Iraq has them and is willing to use them. Yet, over the past three years the international community has done practically nothing to help the Halabja survivors, or the other tens of thousands of Kurds driven out of their country by Iraq’s chemical warfare. Around 140,000 people fled the country in 1988 alone.

This newsletter traces the fate of the Kurdish refugees who have fled the Iraqi gas attacks.

Where Are They Now?

About 100,000 of those exiles are now spending their third winter in crowded, closely-guarded Iranian refugee camps, where food, heating, sanitation, schooling and work are all in short supply. Another 27,000 are living under similar conditions in Turkey. At least 1,500 have moved on to Pakistan, where conditions are not much better. A few thousand — at considerable personal expense — have succeeded in reaching the European Community, entering Greece from neighboring Turkey. Many have been jailed there for illegal entry, as have some of those seeking haven in Pakistan.

Faced with the meagerness of their life in exile, more than 10,0001 Kurds have returned to Iraq, where they have been forced to live in government-planned — and policed — “new settlements” bearing a striking similarity to the refugee camps they left behind. Estimates of how many Kurds are compelled to live in these newly built communities, distant from their original homes, range from a conservative million to more than 1.5 million. Even though they usually returned in response to repeated declarations of amnesty from Saddam Hussein, some of the returnees are known to have subsequently been arrested, executed or “disappeared.”2

Iran and Turkey, though relatively poor themselves, have shown with other refugee groups — such as the Bulgarian Turks and the Afghans — that they can absorb large influxes of immigrants into their economy and society. Neither have done so for the Iraqi Kurds, even though (perhaps because) both countries have significant Kurdish populations of their own. All four of the principal countries of refuge for the Iraqi Kurds — Iran, Turkey, Pakistan and Greece — have tried to unload the problem onto others.

Only two Western countries, the United States and France, have agreed to make a new home for appreciable numbers, and then only for a small fraction of those in limbo at Turkish and Iranian camps. A few dozen more have individually managed to find asylum in the West, either because of close family ties to those countries or by using smugglers and forged papers. Other than these, few of Saddam Hussein’s Kurdish victims — inside or outside Iraq — are leading normal lives.

The Kurds and Kurdistan

The largest ethnic group in the Middle East without their own country, the Kurds now total between 20 and 25 million: a number equivalent to more than the entire population of Iraq, twice that of Syria and several times the number of Palestinians.

The Kurdish diaspora includes several hundred thousand people in the Soviet Union,3 100,000 in Lebanon, and large communities in Germany, Sweden and France. Fewer than 10,000 live in the United States. If the area in which they predominate and have lived for millennia were a separate country, Kurdistan might encompass as much as a third of Turkey, large parts of Iran and Iraq and a sliver of Syria.

That Kurdistan is not a separate nation is due, in part, to its abundant natural resources: two of Iraq’s major oil fields, rich agricultural land, minerals and the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres — one of a series of post World War I agreements which dismembered the Ottoman empire and created the modern states of Iraq, Syria, and Kuwait, among others — offered hope for a Kurdish state around the vilayet of Mosul. Britain later incorporated oil-rich Mosul into its mandate of Iraq.

That unfulfilled promise set the stage for the Kurds’ current plight. As a sizable and frequently rebellious minority group in countries largely populated by Arabs, Turks or Persians, the Kurds — an ancient, Aryan people with their own language akin to Persian — have been perceived as a significant threat by every central government in the region. In modern times, Syria, Turkey and Iraq have all tried to dilute Kurdish claims to a homeland through massive relocation programs. Those countries and Iran all greatly restrict the Kurds’ ability to teach, speak or write about their customs and history in their own or any other language.

With respect to cultural repression, Turkey may be the worst offender. Turkey bans Kurdish entirely,4 even though many of the country’s Kurds only know their own language. Until recently, the government officially pretended that the Kurds — approximately 20% of the population — did not exist. All Kurds have to adopt Turkish names. The official explanation was that they were “Mountain Turks” who had forgotten their Turkish roots.

Two Decades of Persecution by Saddam Hussein’s Regime

Discrimination of the kind described above has, not surprisingly, provoked periodic Kurdish uprisings throughout the region, leading to further repression and persecution.

In early 1970, two years after the Arab Baath Socialist Party seized power in Iraq, Kurdish rebels won several concessions from the state, including the right to autonomy in some of the predominantly Kurdish northeastern provinces and Kurdish representation in the cabinet.

Despite the “March 11” agreement, however, the Baath government excluded the Kurds from real power and persisted with other practices aimed at minimizing the Kurds’ role in national affairs.5 Fighting, which had begun in 1961, resumed in 1974; but this time with the secret backing of the United States, Israel and Iran. Tens of thousands of Kurdish civilians sought refuge in Iran during the course of heavy combat.

However, when the Shah of Iran and President Saddam Hussein signed a border agreement in Algiers in 1975, the United States abruptly withdrew its support for the Kurds and the rebellion collapsed. Many thousands of Kurdish fighters and their families were forced to flee to Iran to escape the pursuing Iraqi army.

Baghdad responded vengefully to the end of the uprising, deporting some 250,000 Kurds — not just the peshmerga families6 — to southern Iraq.7 Because of outrage both within Iraq and in the West, the government later relocated most of the deported Kurds to resettlement camps in the north, closer to the Kurdish cities. In 1983, 8000 men and young boys from the Barzani clan, which had led the fighting, were taken from these camps by soldiers. What happened next remains one of the great unsolved mysteries. All are presumed to have been massacred.

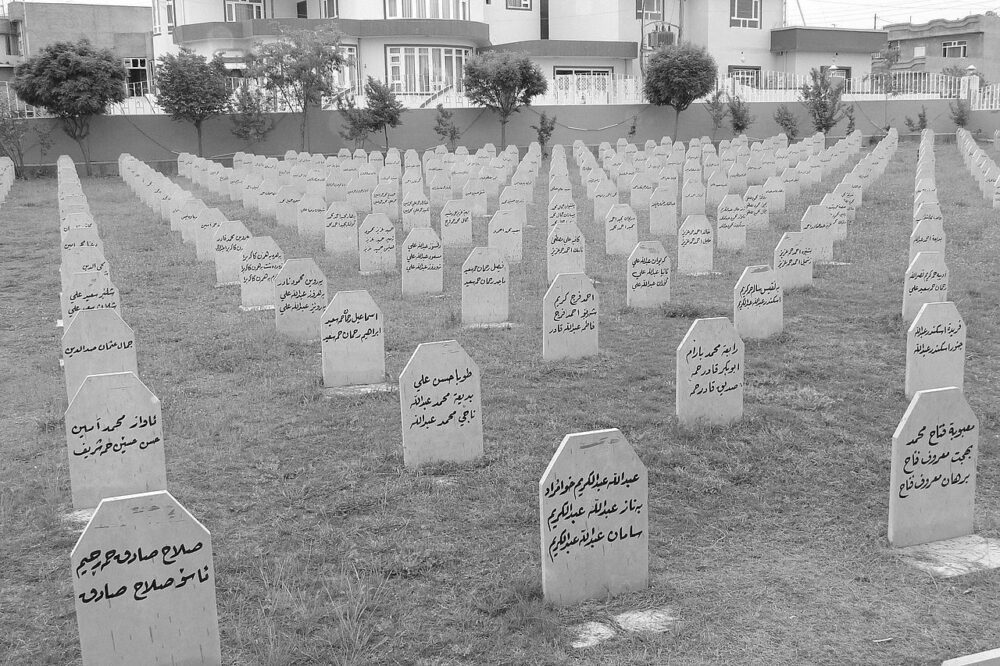

Saddam Hussein, meanwhile, stepped up his campaign to obliterate the ethnic character of Iraqi Kurdistan. Between 1975 and 1989, the government razed more than 3,000 villages and several large towns including Halabja and Qala Diza.8 By the close of this systematic campaign, Iraq had probably uprooted over a million people.

The operation reached a crescendo in 1987 and 1988, after Kurdish rebels took advantage of the long-running war between Iraq and Iran to reclaim 23,000 square miles of their mountain homeland. It was then that Saddam Hussein first began using chemicals weapons on his own people.

I: Chemical Bombings

According to scores of Kurdish eyewitnesses, the bombings of Halabja on March 16 and 17, 1988, were not Iraq’s first use of chemical weapons on Kurdish targets. One commander with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) saw Iraqi warplanes drop poison gas “five or six months” earlier.

It was in the Bargloo area, 20-30 kilometers from the Iranian border, where the PUK had its headquarters at the time. Two or three commanders died five minutes later without injury. I was only about 20 yards away. I had a mask and protective clothing on.9

There are other, unconfirmed reports of chemical bombings as early as April, 1987. Credence that they took place is lent by the fact that the PUK commander in Bargloo says he was already wearing protective clothing — and therefore knew to expect a chemical attack — when his headquarters was hit. In another example, a Kurdish medic treated dozens of chemical weapons victims from Saosenan, a Kurdish village near the Iranian border, shortly before the attack on Halabja:

In this village, 300 or the 400 inhabitants died. They brought the injured to us. They had blisters and burns on their bodies and some had lost their eyesight. Our medical supplies were hopelessly inadequate.10

Besides the fact that the victims had no shrapnel or bullet wounds, the medic says, it was easy to rule out conventional weapons:

I saw aircraft dropping something. The sound was different. In the aftermath, some people lost sight and had problems breathing. It was obvious these were not ordinary weapons.

In some quarters, there remains a dispute over whether Iraq — or both Iran and Iraq — were responsible for the chemical bombings. Most of those pointing the finger at Iran as being the guilty party, despite the enormous propaganda advantage it made of the incident at the time, cite a recent study by the U.S. Army War College, an army-funded military research institute. The study states that:

Iraq was blamed for the Halabja attack, even though it was subsequently brought out that Iran, too, had used chemicals in this operation, and it seemed likely that it was the Iranian bombardment that actually killed the Kurds.11

However, the authors of that internal study, leaked at a time when the Bush Administration was strenuously resisting renewed Congressional efforts to introduce comprehensive trade sanctions against Iraq, cite no authority for their key allegations. In an earlier footnote, the report even notes that Iraq admitted using poison gas at Halabja.12

II: Halabja

What distinguished Halabja from previous, unrecorded incidents was not only the magnitude of the bombardment, but also that journalists were flown in by Tehran to photograph the carnage in the captured town. Because of those pictures, no one could deny that many had been killed by poison gas.

The facts as best they can be reconstructed are the following:

The war between Iran and Iraq was in its eighth year when, on March 16 and 17, 1988, Iraq dropped poison gas on the Kurdish city of Halabja, then held by Iranian troops and Iraqi Kurdish guerrillas allied with Tehran.13 According to the testimony of survivors, the chemical weapons employed in Halabja were dropped from airplanes well after the town had been captured by Iranians and Iraqi Kurdish rebel forces allied with them, and after fighting in the immediate area had ceased.14

The city’s 70,000 or so inhabitants, many of whom were refugees from outlying areas, had already been pounded for two days from the surrounding mountain heights by conventional artillery, mortars and rockets. Many families had spent the night in their basements to escape the bombs. When the gas came, however, that was the worst place to be since the toxic chemicals, heavier than air, concentrated in low-lying areas. Between and 4,000 and 5,000 people, almost all civilians, died either at the time or shortly thereafter.

Hewa, a university student, survived by covering his face with a wet cloth and taking to the mountains around the city. He says that Iraqi warplanes followed, dropping more chemical bombs. “I got some gas in my eyes and had trouble breathing. You always wanted to vomit and when you did, the vomit was green.15 He says he passed “hundreds” of dead bodies. Those around him died in a number of ways, suggesting a combination of toxic chemicals. Some “just dropped dead.” Others “died of laughing.” Others took a few minutes to die, first “burning and blistering” or “coughing up green vomit.” Journalists noted that the lips of many corpses had turned blue.

Hewa and his brother made it to the Iranian border at about 2 a.m. on March 17. Iranian helicopters took them and 48 others to a hospital at Bawa, an Iranian Kurdish town. Later, they were taken to Tehran for further examination. Hewa was in the hospital for four days. After leaving the hospital, he went back to Halabja to look for his family, without success. He was told that those who took refuge in the mountains were taken by government forces.

III: Subsequent Chemical Gas and Conventional Attacks

According to various press and personal accounts, Iraq continued to use toxic weapons sporadically through the summer, as the fighting between Kurdish guerrillas and Iraqi forces helped Iran keep the war at a stalemate.16

The day after Iraq signed a cease-fire with Iran on August 20, 1988, Iraq’s Republican Guards turned on the Kurdish rebels with a vengeance. The heaviest chemical bombing came on August 25. Survivors painted a grisly picture of noiseless bombs producing yellowish smoke smelling of “bad garlic” or “rotten apples”; of people, plants and livestock dying instantly as dead birds and bees fell from the sky. The bodies of the dead burned and blistered and later turned blackish blue.17

Within a month, Iraqi bombs and bulldozers had destroyed 478 villages near the Turkish and Iranian borders, killing 3,496 people according to the Kurdistan Democratic Party.18

The true count may never be known because of the chaos that followed. Tens of thousands of people, many of them women and children travelling on foot, fled for the borders, sometimes a journey of several days through the mountains. The Republican Guards were not far behind, harrying the refugees and continuing to use chemical weapons.

Nerve gas wafting over the Turkish border “devastated honey farms and killed wild flowers and trees,” according to a fact-finding delegation of Turkish parliamentarians.19 Two teenagers who made it to Iran said they saw planes dropping poison gas that killed “more than 3,000” people huddled in the Bassay Gorge in Iraq, about 25 miles south of the Turkish border. The next day, “thousands of soldiers with gas masks and gloves” entered the gorge, dragged the bodies into piles and set them on fire.20

Soldiers cut off about 40,000 other Kurds trying to flee and transported them to detention camps. Reports on these people are scant, since few Western journalists or other foreign delegations have been allowed into the Kurdish region of Iraq, and then under close supervision. Kurdish political sources say that most were initially put in the Bahrka camp near Erbil, and that they and others were later moved to guarded townships around Kurdish cities such as Suleymanieh. The KDP has documented the names of 439 Kurdish men who were rounded up and have disappeared, like the 8,000 Barzanis in 1983.

Turkey’s Government Under Pressure

By August 29, 1988, thousands of Iraqi Kurds had reached the Turkish border, only to find their passage blocked by Turkish troops. For two days, as their numbers swelled, Turkey refused to let them in.

Relations have never been good between the Turkish government and its own sizable Kurdish population, who form the vast majority in the country’s southeast region near the Iraqi, Iranian and Syrian borders. Since 1984, Ankara has been trying to suppress a guerrilla war by the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), a Marxist-oriented group seeking an independent Kurdish state. At least 2,600 people have died in the conflict, according to regional governor of the southeastern provinces, Hayri Kozakcioglu.21 Not only the PKK but all Kurdish political groups are outlawed in Turkey.

At the very end of August, after several parliamentarians from the Social Democratic People’s Party (SHP), the leading opposition party, flew to the border to make their own report, Prime Minister Turgut Ozal bowed to growing domestic and international pressure and announced he would open the border “on humanitarian grounds.”22

For several weeks, the refugees camped on the ground in several sites near the Iraqi and Iranian border. The Turks provided them with food, but no tents or blankets for at least a week. Since most escaped on foot, few had any clothes other than what they wore. The night air in the mountains was already cool and many were still suffering from the effects of the chemical attacks.

From the outset, Turkey tried to pass on the problem to other countries. Even before it officially opened the border, the army began trucking refugees involuntarily to Kurdish towns in Iran.23 Within a week after offering them safe haven, the government had loaded about 2,000 Kurds onto buses and lorries. Turkish soldiers guarding the group “beat us to try to get us to go,” says one refugee who refused to get aboard.24 Journalists at the scene also reported that many of the Kurds were coerced into leaving.25

Over the next six weeks, the numbers leaving for Iran climbed to at least 20,000. Journalists reported that Turkey had smuggled many of them over the border without even notifying the Iranian government.26 By mid-October, some reports indicated that cold more than coercion had become the driving force behind the refugees’ decision to go peacefully to a third country.27 Most of those leaving had been quartered in two tent camps near Yuksekova, a region with 13,000 foot mountain peaks and winter temperatures falling well below freezing. However, refugees also told a Financial Times correspondent that Turkish soldiers had “urged them to move on down the road (to Iran) if they did not want to return to Iraq.”28

By the end of the year, approximately 36,000 of those in the original exodus to Turkey, estimated at over 60,000 people, remained. Since then, a few hundred have moved on to Syria with the help of the Turkish government, according to Akram Mayi, a leader of the camps in Turkey. According to Mayi, another 4,000 to 5,000 have made their way illegally to Greece. A similar number moved back to Iraq on their own in late 1988 and early 1989. That leaves about 27,000 people still in three Turkish refugee camps (Diyarbakir, 11,000; Mardin, 11,300; and Mus, 4,600), all in the Kurdish southeastern part of the country.

I: The Kurdish Refugees’ Status in Turkey

In strictly legal terms, Turkey considers the Iraqi Kurds “guests” rather than “refugees” as defined by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocols (“Convention on Refugees”) — the main international law dealing with those fleeing persecution. Turkey has signed the convention, but with the significant stipulation that it only apply to people fleeing from Europe.

The ramifications for the Kurdish exiles are enormous. If they were “refugees” and not “guests,” they could settle wherever they wanted in the country. The government would have to issue travel documents allowing them to go abroad and to move freely within Turkey and would be obliged to “make every effort” to expedite naturalization proceedings.29 Turkey would not be able to restrict their employment opportunities any more than it does for other resident aliens and would have to provide elementary-level education.30

If they were recognized refugees, they would also be under the protection of the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). The UNHCR has been given only limited access to the camps on a discretionary basis. It has no authority to collect or distribute badly-needed relief supplies or to protect individuals from mistreatment or refoulement (involuntary repatriation) to Iraq.

As it is, the Turkish government has provided the refugees with basic food, shelter and medical care but has consistently made it clear they should not think of Turkey as a permanent home. Largely confined to their camps, they have restricted work opportunities and very little freedom to leave the immediate camp vicinity.

There were no schools for the children in two of the camps for more than two years. Now they are little better off: they have untrained Turkish teachers attempting to teach students in Turkish — a foreign language to the Iraqi Kurds. The government forbade the refugees from setting up their own schools in Kurdish, though at one camp it acquiesced after the Kurds proceeded on their own.

II: A Striking Contrast in the Treatment of Refugees

To the Iraqi Kurds, their inferior status was graphically demonstrated by the arrival in Turkey of another large influx of refugees less than a year after their own flight. The second group was treated very differently.

In the summer and fall of 1989, Turkey took in 379,000 ethnic Turks from Bulgaria — ten times the number of the Iraqi Kurds remaining. Ironically, the Turks had left Bulgaria because of the same sort of persecution to which Turkey was subjecting its own Kurdish population: forced resettlements, mass arrests, and a ban on the use of their native language, traditional names, music and customs. Just as Turkey claimed that its Kurds were only “mountain Turks,” Bulgaria claimed that its Turks were only restoring their ancient Bulgarian names after being forcibly “Islamicized” under the Ottoman empire.31

Though Turkey initially established reception camps for the Bulgarian Turks, they were free to travel, to settle and work wherever they wanted. Public schools developed special language classes for the children, even though most could already speak, if not write, Turkish. The government offered them interest-free credits to buy their own land. In less than two years, many of the 240,000 who remain have become Turkish citizens and most have been fully assimilated.

At one point, the Turkish government even considered a plan to give the Bulgarian Turks thousands of acres of land in the Kurdish southeastern provinces — not far from the camps where the Iraqi refugees are required to live, 8-10 to a room or 16 to a tent. Turkey officials lobbied the U.S. Congress to get financial assistance for the Bulgarian Turks. “The Turks assiduously avoided any discussion of the Iraqi Kurds,” says Meg Donovan, a staff member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.32

Going on the offensive, Turkey’s Prime Minister Ozal accused Western countries of applying a double standard. “The West gets excited over human rights in Turkey when Europeans are involved, but doesn’t give a damn when Turks are the victims,” he was quoted as saying in reference to the Bulgarian Turks.33 In fact, the story did get a great deal of attention in the West, most of it favorable to Turkey. The real issue of double standards, vis à vis the Kurds, seems to have escaped his notice.

III: Conditions in the Turkish Camps

By the winter of 1988-1989, Turkey had consolidated all the refugees into three camps. Two of them, Diyarbakir and Mus, consist of concrete apartment houses originally built for victims of an earlier earthquake. The third, near Mardin, is a tent camp. Each is run by the local Turkish governor’s office.

A Middle East Watch mission visited the Diyarbakir and Mardin camps in November 1990 — the first outside group allowed in that year. Descriptions of the three camps comes from that visit as well as from interviews with refugees outside the camps and earlier reports by journalists and humanitarian groups, including Helsinki Watch.

Mardin

By most standards, this tent camp is the least desirable of the three refugee settlements. According to the assistant governor of Mardin province, as of October 1990, the camp held 11,333 people — more than 6,000 of them under the age of 14.34

The camp is made up of several hundred large tents, lined up in rows, with shallow water trenches running between. Though the entire encampment had been surrounded by barbed wire, it apparently had been taken down sometime before the Middle East Watch visit in mid-November 1990. There are only two permanent structures: one building with an infirmary and offices for the Turkish camp authorities and another with storage rooms for medicines and food. A few police or soldiers with rifles guarded the perimeter.

The people in Mardin generally looked gaunt and unwashed. Even though the weather was becoming cold, many children did not have shoes. Hordes of malnourished-looking children played with a ball in a dirt area between the tents and the road. We did not see any other toys. A large pit in their play area, created when the refugees made mud bricks to reinforce the tents, looked hazardous for young children.

The camp authorities showed us one of the tents. It consisted of two rooms, of about 2.5 by 3.5 meters and 2 by 2.5 meters respectively, each holding one family. This was home for some sixteen people. The canvas was two-ply, with a few holes; it was not clear if the layers kept out the elements.

Around this tent, as most of the others, the refugees had built a low wall of home-made mud bricks. The entire furnishings consisted of 15 blankets, about eight thin mats, a small stove used for both cooking and heat, five pots, a few dishes, some food supplies and a small cassette tape player. Other than the last item, which was obviously not state-issue, it was not clear what the state had provided and what the refugees had bought themselves.

Cold weather has been a grave problem, according to camp leaders, who say that the government has given the refugees only two blankets per family. Temperatures in the region can be extreme. During the mission’s visit, on a moderately chilly evening, the government had already distributed wood for the stove and the tent inspected was comfortably warm. However, camp leaders say the wood supply, one ton per tent for the winter, is not enough.

Clothing is apparently also in short supply. Few of the children we saw had socks and many did not have shoes. Camp leaders said that the government gave the adults plastic shoes which were “very simple and cheap.” Last year, the Turkish authorities also passed out clothing material — five meters for each woman, one meter for every six men and none for the children — and three sewing machines. “We were able to produce just 400 trousers and shirts,” says one camp leader. That comes to approximately one suit of clothing for 28 people.

The refugees also complain about sanitation. Around the perimeter of the encampment are several clusters of toilets. The refugees say two-thirds of them are usually backed up. There are no bathing facilities. Even the Turkish officials running the camp admit that people must wash outside, by the side of the tents, even in winter. “They are not accustomed to modern baths,” said the assistant Mardin governor. “It is against their tradition.” The Kurds’ leaders dispute this patronizing remark.

The water comes from 162 faucets at different points around and inside the camp. Refugee representatives claim that 70 percent are broken, that water flows only at a dribble and is occasionally cut entirely. “The women sometimes have to stay in line three or four hours to fill their bottles,” says a refugee spokesman.

The run-off water flows into several shallow, open trenches that run between the rows of tents — a potential health problem in summer. It is hard to walk anywhere without stepping into a trench.

The Turkish government provides free health care. The Mardin camp, like the others, has an infirmary with Turkish doctors and nurses. Several people were queued up outside. The officials showed us a large pharmacy. Camp leaders say that health care is adequate, “except that the doctors are not very well-trained.” There were originally two Kurdish doctors among the refugees, but they have since moved on to France. Several trained nurses remain. Officially, they are not allowed to practice.

The government also provides food rations, which should be adequate if delivered according to the official figures. According to Ozdemir, the bi-weekly ration per person comprises:

2 kilograms of rice; 2 kg of bulgar (cracked wheat); 1/2 kg of nohut (chick peas); 1/2 kg “special” macaroni; 1/2 kg macaroni; 1/2 kg tomato juice; 1/2 kg jam; 1/2 kg olives; 2 kg powdered sugar; 1/2 kg margarine; 1/2 kg of meat; 1/2 kg tea; 1 kg dried beans; 1/2 kg soap; 1 kg detergent; 1/2 kg canned meals; 300 grams salt; 2 kg potatoes; 1 kg dried lentils; and 1 kg of onions.

In addition, he said, each child is allotted two kilograms a month of dried milk and, according to the season, everyone gets fresh fruit and vegetables.

The camp leaders dispute the official figures. They say the refugees once received some grapes but otherwise have had no fresh fruit or vegetables in more than two years, other than what they can buy themselves. They say each tent receives only one kilogram of meat every two to four weeks. Since the camp authorities only gave mission participants a half hour alone with the camp leaders, it was not possible to reach firm conclusions regarding the accuracy of the food list.

Supplementing their supplies has been very difficult for the Mardin residents because of tight restrictions on their ability to leave the camp. Assistant Governor Ozdemir claims that everyone who wants to leave is usually able to do so. But according to camp leaders, as of last November, only 300 of the 11,000 people in the camp could usually leave during the daytime on any given day. Those who wanted to leave would put themselves on a list submitted to the Turkish camp police. Only a fraction of those listed were actually allowed out and decisions were often arbitrary. “If the policeman is kind, he may let 1,000 out, but if he is not, he will limit it to 300,” said Zubeyir Mayi, head of the Mardin refugees’ committee.

Such restrictions make it difficult for the refugees to earn any money, though some are able to get occasional day jobs in construction or on farms. Mayi said they were not allowed to go to Mardin, the nearest city, though the trip is out of the question financially for many of the refugees. It costs 2,000 Turkish Lira — about 60 U.S. cents — each way, perhaps 20 percent of what a refugee might earn in a day, if he could find a job. Unemployment is high in the region.

Unlike in the other camps, Turkish authorities have let the Mardin refugees set up their own classes for the children in Kurdish. These schools started secretly in May, 1989. By November 1989, 50-60 refugee teachers, using 17 tented classrooms, were giving classes for more than 2,000 students, with the knowledge of the Turkish camp authorities.

The school tents, donated by local Kurds, are only about twelve square meters. To accomodate all the children, teachers must work several shifts. Pencils, paper and chalkboards also came from local donations. There were no books and teachers say that Turkey’s Kurdish language ban makes it difficult to find suitable teaching materials.

Diyarbakir

Diyarbakir, the best of the three camps, is an apartment city of 71 concrete buildings housing 11,000 refugees. When Middle East Watch visited in November, 1990, children had pulled down much of the barbed wire — laundry was hanging out to dry on some of the fence — but a guard post still restricts entry. Within the camp is a large school building and a concrete playground the approximate size of a football field. Near the school, several dozen refugees have set up produce stands, selling a large variety of fruits and vegetables. The people look much better fed and more energetic than the refugees in Mardin.

Each building holds six identical apartments. Each unit has six rooms: three chambers, a small kitchen, bathing room and toilet — about 40 square meters (431 square feet) altogether. It would be adequate living space for one family, but each unit usually holds one family per room, 25-30 people in all. For lack of space, many groups have turned the kitchen into sleeping quarters.

During their first year in the apartments, the refugees did not have electricity. Now one sees ceiling fans in many of the chambers. Some families have built bunkbeds or storage cubes. When they first arrived, the human rights association in Diyarbakir and local Kurds donated mattresses and blankets. But there is no room for furniture.

Unlike the camp in Mardin, sanitation is not a problem. Each apartment has running water, though the refugees say it only runs at night and they must store it in bottles for the day. The do complain that the water is not very good. “The Turkish officials who work in the camp don’t drink it,” says Akram Mayi, a camp leader.35

The food rations supplied by the government are similar to those in Mardin, though the people in Diyarbakir seem to get meat more often. “There are many things people should eat we don’t get,” says Mayi. “But the food is good compared to what the local people can afford to eat.”

He says the same of the health care, which is free. The camp has an infirmary that occupies two apartments. One is used as an examining room; the other has beds and a pharmacy. Eight young doctors — part of a national health internship — staff the facility. More serious cases are sent to the local Diyarbakir hospitals.

The government has supplied the refugees with clothes twice in two years, according to Mayi. Each man has received one pair of shoes, one shirt and one pair of warm underclothes each time. The women got two pieces of fabric and one pair of shoes. The children all received a shirt and only some got shoes. It is not enough, say the refugees.

Like those in the Mardin camp, the refugees in Diyarbakir opened a school for their children in May 1990. Using trained teachers among the refugees, they ran twelve classes, in Kurdish, in the basements of the apartments. It only lasted five days before the camp police closed them down.

From the beginning of their stay in Turkey, says Mayi, the refugees had petitioned the president, regional governor and other officials to allow them to open a Kurdish school. They received no response. After their classes were shut down, they tried again and this time the governor of Diyarbakir said they could have classes, but only in Turkish. Deciding that any school was preferable to none, they petitioned for a Turkish school. The school principal and regional governor all told Middle East Watch that the refugees really wanted Turkish classes all along.

Middle East Watch had a chance to see how well the Turkish instruction was working. Thirty-six Turkish teachers (plus four administrators) were running classes, in three shifts, for 1,728 students, aged seven to 12. The curriculum, we were told, would be identical to that used in schools throughout Turkey. Unlike most Turkish children, however, the Iraqi Kurds don’t know Turkish and only one teacher, a Kurdish Turk, knew Kurdish. There was no provision to teach the children the new language.

We were there during the second week of classes. Communication between teachers and students was rudimentary. In one week, we were told, the students had been taught where to sit and what time to arrive for class. In one classroom, a young boy helped translate for the teacher; he had picked up some Turkish phrases while working in town.

Many of the refugees in Diyarbakir, unlike those in Mardin or Mus, have been able to supplement the government hand-outs by earning money in town. When Middle East Watch visited southeastern Turkey in November 1990, government buses were taking several busloads of people to Diyarbakir and back every day, a ten minute ride. Dozens of refugees could be seen in Diyarbakir peddling wares: socks, batteries and, their specialty, Kurdish tapes.36 Some of the men had found temporary construction jobs. Local Kurdish merchants have been quite supportive. Many of them give goods to the Iraqi Kurds on consignment and split the profits from any sales. Local farmers also supply the produce for the camp vegetable stands.

However, the freedom has important limitations. “I have been in Diyarbakir for almost two and a half years and I haven’t been allowed out of the city limits,” Salih Haci Huseyin, one of the Diyarbakir camp leaders, told Middle East Watch during a clandestinely-held meeting in Diyarbakir in November. “We are allowed out from sunrise to sunset and have to pass through several stages of permission.”

For several months after they arrived at the camp, authorities would only let out the sick, then only a few a day. “It was impossible to work because you couldn’t get out on a regular basis,” says Huseyin. The rules were relaxed when the authorities discovered that the Iraqi refugees were not getting involved in the local Kurdish protests and uprising.

The freedom is also fragile. One day during our visit, the authorities closed off the camp for a head count. According to Kurdish sources and journalists, Turkey has sealed off all three camps entirely since January 17, with the start of the Persian Gulf War.

Mus

Less is known about the Mus camp, which houses 4,600 refugees, largely because it is a five or six hour drive from Diyarbakir, the nearest city with a commercial airport. In addition, the authorities have restricted the refugees from leaving — and outsiders from entering — to a greater extent than with either the Mardin or Diyarbakir camps.

The Iraqi Kurds in Dyarbakir and Mardin, about one and a half hours’ drive apart, often visit each other. Such interchange with the Mus camp is rare. No outsiders were allowed in the camp for the first 11 months of 1990. Before the summer of 1990, according to a refugee spokesman for all three camps, Turkish guards allowed only 70 to 80 people out of the camp per day to shop, and then only for four or five hours. Control was then relaxed for a few months and the refugees were generally allowed out to find work. But, as at the other camps, the authorities locked the gates again at the start of the war with Iraq.

The Mus complex has 500 one-story-houses, each with two flats of 75 square meters (approximately 800 square feet). As in the other camps, there is free food and an infirmary. The government provides fuel for heat, but a refugee spokesman says it is insufficient.

Deaths were high in the Mus camp at first. An international mission visiting there in March and April, 1989 reported that 349 people had died in the preceding eight months, 269 of them children — proportionately four times the number of deaths in the Mardin camp.

According to Akram Mayi, the Kurds at the Mus camp also opened their own Kurdish schools, though not until late spring, 1990. “They finished the first course,” says Mayi. “At the beginning of the second, the police closed the schools and opened ones in Turkish.”

IV: Refoulement

Refoulement — forcing a refugee to return to a country where his life or freedom would be threatened — is specifically banned by the Convention on Refugees and also by customary international law.37 Turkey may have done more than show disinterest in keeping the Kurdish refugees. Several of the refugees — as well as international monitoring groups such as Amnesty International and the UNHCR — claim that Turkey pressured them to return to Iraq, and may even have forced some to leave despite the growing evidence of danger at the hands of the Iraqi authorities.38

Iraq offered five amnesties between September 1988 and July 1990, two specifically aimed at the Kurds. It is not at all clear why the Iraqi government would want them back, unless it were to save face and protect their already tarnished international image. “We make big propaganda against the Iraqi regime,” explained one refugee in Turkey.39 Since many in the camps had been peshmergas — the Kurdish word for their fighters — some speculated that Iraq wanted them back to arrest or execute the insurgents. In all, however, at least 5,000 Kurds from the Turkish camps responded to the Iraqi offers.40

According to reports received by those still in Turkey, many returned to camps much like the ones they left in Turkey. Some, especially among those who returned last summer, may have been allowed to live in Suleymanieh, Erbil or other remaining Kurdish cities. Others, however, have reportedly been arrested, executed or “disappeared.”

Amnesty International says that several hundred people might have been forced back in the initial months after the mass exodus of late 1988. One thousand or so Iraqi Kurds agreed to be repatriated after Ankara invited the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to insure their safety. Iraq, however, objected to this arrangement, the ICRC pulled out on October 2, and many of the refugees changed their minds.

Given their hostile welcome in Turkey and the forcible transportation underway to Iran, 1,400 Kurds, despite all their fears, decided to leave for Iraq on October 6.41 It is not clear why more left than originally signed up. Turkey’s decision not to give the Kurds refugee status — thus giving them dim prospects of ever developing a normal life in Turkey or going elsewhere under UNHCR auspices — may have convinced many to try their chances again in Iraq.

However, some refugees in the Turkish camp later told Amnesty International that “some of those who changed their minds were nonetheless forced onto buses bound for Iraq.”42 According to the same Amnesty report, at least three of those Kurds are known to have disappeared after entering Iraq.

Others who returned under subsequent amnesties disappeared as well. At least 67 Assyrians who returned to Iraq after joining the Kurdish flight to Turkey are reported missing by their families.43 Iraq also reportedly executed four ethnic Turks who had returned from the refugee camps in Turkey.44

Early in December 1989, Iraq demanded the extradition of 138 Kurds in the Turkish camps, saying they were wanted on criminal charges. In response, on December 12, 1989, Turkey’s national police arrested one man from the list, Mohammed Simmo, a peshmerga leader from one of the camps. The next day, he was seen in the custody of Turkish police at a checkpoint near Habur and a few hours later, with Iraqi and Turkish police escorts at the Iraqi border town of Zakhu. He later escaped to Iran.45

Forty-six others were forcibly repatriated that December and January, according to Amnesty International.46 Amnesty reports that Turkish camp authorities mistreated two of them, Muhammad Tawfiq and Haji Arafat, until they signed statements saying that were returning voluntarily.

The refugees argue that many of those who returned to Iraq did not do so freely, even if they were not physically coerced. Pressure, they say, came from both Iraq and Turkey, sometimes in collaboration. Iraqi propaganda agents, the refugees claim, had free run of the camps. Several refugees claimed they had known these people in Iraq. The pressure on camp organizers was especially intense. One said Iraq sent a relative of his to Turkey to bring him back.

Another told Middle East Watch:

They took my father and brother to the police station in Dohuk [a Kurdish city in Iraq] and made them call me to say the situation in Iraq is good and that I should come back. My uncle later called to tell me to ignore the other calls.47

Camp leaders also report getting reassuring phone calls from some of those repatriated claiming they had been allowed to return to their native villages — settlements believed to have already been completely destroyed at the time of the call.

V: Bread Poisoning

The refugees blame Iraq and Turkey for three mysterious large-scale poisonings: June 8, 1989 in Mardin, December 17, 1989 in Mus and February 1, 1990 in Diyarbakir. No one has proven the involvement of either government, though Turkey did block independent investigation of the matter.

The three events were remarkably similar. Following a new delivery of bread, several hundred people fell ill: about 2,000 in Mardin, 100-200 in Mus and 700-1,000 in Diyarbakir. Few died — only one in Diyarbakir and two in Mardin — but several hundred people were hospitalized. Though the bread for each of the camps comes from different bakeries, the victims all had similar symptoms, including abdominal pain, sleepiness, diminished vision and difficulty breathing. Several women miscarried.

Turkish authorities did little to unravel the mystery. Local governor Cengiz Bulut promptly blamed the Diyarbakir poisoning on moldy bread. And while Turkish Health Ministry officials said they found no poisonous substances in the loaves, they would not allow an independent analysis of samples. A spokesman for the Turkish Foreign Ministry suggested that the illnesses were psychosomatic. “When they have a stomach ache, they could be panicking into thinking they have been poisoned,” he said.47

Each time, authorities sealed off the camp and refused to let outsiders investigate. Turkish journalists and independent scientists were also turned away from the hospitals where victims were being treated. There were even reports after the Mardin incident that some patients were sent back to the camp while still seriously ill.

Shortly after the Mardin incident, however, two Britons — journalist Gwynne Roberts and Dr. John Foran of the London-based organization International Medical Relief — managed to obtain bread and blood samples from a local Kurdish contact. A scientist who analyzed the blood samples at London’s New Cross Hospital says he found “unmistakable signs that the blood enzymes had been attacked by a supertoxic organophosphate,” a potent nerve agent. In a letter published in the February 3, 1990, issue of The Lancet, a highly respected British medical journal, four British scientists concluded: “It is unlikely that we are talking about a common commercially available chemical, so that the chance of accidental poisoning is remote.”49

Claims by the refugees that Iraq was behind the poisoning are all circumstantial; they say an Iraqi delegation had visited the camp shortly before the poisoning. Iraq does, however, have extensive experience of poisoning Kurdish opposition figures; 40 were poisoned in separate incidents in late 1987 alone.50 Most of those received thallium, which the British teams ruled out as the toxin in the Turkish bread. But informed Kurdish sources also claim that Iraq has extensively experimented with other sophisticated toxins.

VI: Efforts to Resettle the Refugees

Turkey has half-heartedly pursued two, more permanent, solutions for this embarassing problem — the building of better quarters elsewhere in Turkey for the Kurds, and finding them a home in the West — neither with great success to date.

In the fall of 1989, the government began negotiating with the UNHCR for help in raising $13.2 million to build prefabricated housing units in Yozgut, about 220 kilometers east of Ankara on the central Anatolian plain, for those still living in the Mardin tent camp. However, by April 1990, when the UNHCR announced that it had raised $14 million in pledges (much of it from the U.S. government), Ankara was no longer interested.

Why not? A Turkish Foreign Ministry spokesman told the Financial Times that the people of Yozgut had formed committees to stop the project. Besides, he added, the Kurds (whose leaders had not been consulted about the proposed resettlement effort) did not want to settle in Yozgut.51

The planned site was far from the predominantly Kurdish southeastern provinces. But why did the government not pick a more suitable location in the Kurdish southeast? “The government may have thought that integrating the peshmerga into a region where a lot of fighting is going on might not be a good idea,” speculates UNHCR officer Henrik Nordentoft, adding that “most of the land is locally-owned.”52 What remains unclear is how Turkey could have contemplated providing land in the Kurdish provinces to the Bulgarian Turks if the latter explanation is a reasonable one.

Since halting the Yozgut project, Turkey has renewed efforts to place large numbers of the refugees in Europe or America. Last summer, the United States agreed to accept 300 families — estimated at about 2,000 people in all. France, which took in 355 people in honor of the 1989 bicentennial of the French Revolution, has promised to take another 600. No other country has responded to the appeal. One hundred of the additional 600 have made it to France. However, because of the Persian Gulf War, the arrival of the 2,000 scheduled to come to the United States this month was delayed.

Iran: A Reluctant Host

According to most accounts, at least 370,000 Iraqi Kurds have sought refuge in Iran since 1971, more than 100,000 of them in 1988. Given that the entire Kurdish population of Iraq is estimated at 3.5 million, this means that over 10 percent of all Iraqi Kurds are presently being housed by their eastern neighbor.

Iran is in many ways a logical haven for the Kurds. Unlike those in Turkey, the Kurds of Iran and Iraq share the Arab alphabet, which makes printed material in Kurdish mutually intelligible. Most Iranian Kurds also understand the southern Kurdish dialect spoken in Iraq. Many families and tribes straddle the border and have been generous in helping the refugees.

In contrast to Turkey’s rough ride, the Iranian government has received little criticism — and some commendation53 — over its treatment of the Kurdish refugees. However, this is probably due less to Iran’s greater hospitality towards the Kurds than the greater restrictions it imposes on Western journalists and other independent monitors.

As with Turkey, Iran’s welcome had limitations. In the first week of October 1988, Iran closed its border to Turkey after Ankara secretly transported thousands of Kurdish refugees to nearby Iranian provinces.54 A few days later, the Tehran government agreed to accept more that 100,000 of the refugees because of “Islamic and humanitarian principles,” but not before the spring.55

Middle East Watch interviews with refugees indicate that Turkey’s accomodations and provisions for the refugees, widely criticized by the scores of journalists and monitors allowed in the camps, in many ways surpassed Iran’s largesse. Iran, however, has not given journalists a chance to make the comparison.

One strong indication of the poor conditions in Iran came when several hundred refugees who had opted to leave Turkey for Iran in 1988 showed up in the UNHCR office in Ankara, begging to be allowed back.56 On the other hand, going back to Iraq has often been even worse. Refugees in Iran say that some of those who returned under the early amnesties announced by Baghdad found conditions in their homeland so intolerable that they went back to Iran again.57

What little is known about this overlooked mass of refugees has therefore been largely pieced together from reports by the UNHCR and Kurdish political organizations and from interviews with a handful of Iraqi Kurds who have escaped to the West. Their depictions of conditions are often at variance and far from complete.

I: Previous Waves of Kurdish Refugees

Between 1971 and 1980, Iraq expelled at least 200,000 Faili Kurds. Unlike most Iraqi Kurds who are Sunni Moslems, the Failis are Shi’a and lived mainly in the Arab-dominated region of central Iraq. Many Faili Kurds had been wealthy businessmen and controlled large parts of the Baghdad bazaar. Although the real grounds for persecution were probably economic, the government used the Faili Kurds’ religion as a pretext to claim they were really Iranian — Iran being a Shi’te country — and should therefore move.

Some 250,000 other Kurds sought refuge in Iran in 1975, after the collapse of Mulla Mustafa Barzani’s rebellion in northern Iraq, according to a KDP spokesman. Most returned to Iraq during various amnesties offered by Iraq between 1975 and 1979, but about 50,000 remain in Iran.58 Today, they share at least one camp with other KDP peshmerga families who came in 1988. Another 25,000 Kurds came to Iran in dribbles, often because of individual or family disputes with the Baathist regime, between 1971 and 1989.59

The chemical bombings in 1988 added more than 100,000 people to Iran’s population of Iraqi Kurdish refugees.

II: The Response to Halabja

On the political and, to some extent, humanitarian planes, Iran’s response to the plight of the Iraqi Kurds has been positive. After the bombing of Halabja in March 1988, Iranian helicopters were waiting at the international border to ferry wounded Kurds to medical stations. Admittedly, Iranian forces were engaged at the time in a battle with Iraqi troops, and thus were doing little more than helping wartime allies and their families. That September, when busloads of displaced Iraqi Kurds began to turn up on Iran’s borders from Turkey, Tehran publically welcomed them as well as those who made their own way to Iran. Unlike Turkey, Iran has not tried to force the Kurdish refugees to return to Iraq.

At least 50,000 Iraqi Kurds crossed the Iranian border after the bombardment of Halabja in March 1988. Others put that figure as high as 70,000. According to the UNHCR, 38,000 more arrived after Iraq’s August assault, most of them via Turkey.60 Still other Iraqi Kurds sought refuge in Iran in the spring of 1989, when the Baath government razed the Kurdish city of Qala Diza.

As of the spring of 1990, about 100,000 of the Kurds who fled during the chemical gas attacks in 1988 remained in Iran. Those numbers probably included at least 10,000 who came in the fall of 1987, when fighting along the border was intense. Some may have also fled from chemical attacks.

These numbers reflect a significant amount of attrition: according to the UNHCR, as many as 45,000 of the refugees, mostly from Halabja, took up Iraq’s first amnesty offer in September 1988.61 Several thousand more returned to Iraq during the other amnesties offered between December 1988 and July 1990. Last summer, theWashington Post reported that a number of Iraqi Kurds who had moved on from Turkey to Iran in 1988 subsequently returned to Turkey after getting a taste of the alternative.62

More recently, the numbers in Iran have been swollen somewhat by those who fled the allied bombing of northern Iraq in January and February 1991. According to official United Nations counts, more than 3,000 people — Iraqi Arabs and Kurds as well as foreign nationals — sought refuge in Iran during the first month of the Gulf War. Iranian sources abroad say that dozens of other Kurdish families clandestinely slipped across unguarded sections of the border in the first weeks, taking refuge with Iranian Kurds.

III: Conditions in the Camps

Although many of the Iraqi Kurds remain in camps, they have been assimilated into the local communities to a much greater extent than in Turkey. Part of this was by necessity. Exhausted by its eight-year war, in late 1988 Iran was unprepared for the arrival of 100,000 people — most of them without any money or possessions. The tents it provided were inadequate protection against the bitter mountain winters. Temperatures in the border region can reach minus 20-30 degrees centigrade. With the onset of cold weather, local families took in many of the refugees.63 Others sat out the first winter in neighborhood mosques, warehouses and stables.64

By the summer of 1989, Iran had distributed most of the refugees into 23 small camps, 13 towns and 157 villages and towns in three border provinces with large Kurdish populations: Azerbaijan, Kurdistan and Bakhtaran.65 In addition, the government established at least one camp near Tehran for single men.

Descriptions of the facilities are scant, but it seems that conditions vary enormously. An international agency which toured several campsites in May 1989, reported that a quarter of the refugees in Baktaran and Kurdistan and half of those in West Azerbaijan were still living in tents. Fifteen hundred families in Urumia stayed in tents all winter. Many of the permanent houses being built for them — 75 percent in Bakhtaran, 65 percent in the city of Sanandaj and 25 percent in West Azerbaijan province — were not finished. Most lacked electricity, water and toilets.

The delegation reported that the new accomodation was crude. The refugees themselves did the construction with mortar and bricks provided by the Iranian government. In one camp it visited, the Kurds had constructed uniform rowhouses, each consisting of two rooms of twelve square meters — one per family — and a nine square meter kitchen. Plastic sheeting was used to cover the window frames. A small kerosene stove served for both cooking and heating. The government provided fuel sometimes, but the refugees also had to purchase it themselves.

Sanitation appears to have been a problem in the two camps the agency visited. Of one, mission members reported:

The latrines are open pits with a burlap screen. Water is brought to the camps by truck or from wells… about 50 liters of water is given to each family every second day.

In another camp, the group reported a “lack of water and few latrines.”

The Iranian government and Iranian Red Crescent provide basic food for the refugees, at least for those in camps. The High Administrative Committee for Refugees, a relief group organized by Iraqi Kurds, complained in an August 1989 report that:

Shortages in foodstuffs and delay in delivery are common. The monthly rations are not sufficient to sustain the recipients for a whole month. The rations, in addition, made up a limited number of foodstuffs… Hunger is not unknown.

According to the report, those living in towns and villages did not even start receiving rations until 1989.

Food distribution was erratic and varied greatly by province, according to the Kurdish relief committee. In Bakhtaran, the refugees received ration cards to obtain staples soon after they arrived in 1988; in Kurdistan, they did not get them until the next year. In West Azerbaijan, “hundreds of families” were still without the cards in the summer of 1989 and “in this province, the food is often sold to the refugees.” The international group which visited in May 1989 also found that the refugees had to buy meat and vegetables, often at a high price: 500 Rials for a kilogram of potatoes and 300 rials for onions.

IV: A Shortage of Cash and Work

Money for necessities has not been easy to come by. Some of the wealthier Kurds brought cash or jewelry with them from Iraq and the Iraqi Kurdistan Front, the coalition group representing five Kurdish guerrilla organizations, distributed about $800,000 — $100-$200 a family — shortly after the exodus. Those personal and relief funds, however, were quickly exhausted.

Most reports concur that few of the refugees are working. In July 1990, the UNHCR office in Iran cabled to headquarters that employment among those in the Kurdish refugee camps was “negligible.” A UNHCR investigator described life at Gualyaran, a camp in Bakhtaran province holding 2,430 people, as “a constant struggle of hope against resignation.” While some people were busy building a mosque for the settlement, the writer was struck by the men “with seemingly nothing to do, lost in thoughts of their future.”66

One obstacle seems to be the high unemployment rate in the Kurdish provinces. The area has been economically neglected for decades, under both the Shah and Islamic government. An international delegation visiting two camps near Bakhtaran — Serias and Rawanzar — in May 1989, found it possible for the refugees to take casual jobs, but noted that there were few available in the area.

More serious, however, are government restrictions on the employment of refugees. According to the UNHCR’s Tehran office, no employment is possible without sponsorship from either the government or an employer and without such sponsorship, refugees are not allowed to leave the camps. The international group visiting in May 1989 reported that to leave “a permission is required…” but was “generally granted.”

Others, however, paint a different picture. H.R., a former refugee in Iran interviewed by Middle East Watch, says that those at his camp near Tehran were usually only allowed out three days a month and he did not receive such permission at all for seven months.

V: Education

The UNHCR in Tehran last summer described education as the area with the greatest discrepancy between needs of refugees and means to satisfy them. Many, if not most, of the refugee children have been without schooling for more than two years now. Older youths are barred from Iranian universities altogether.

Reports on whether the Kurdish refugee children are entitled to enter the local Iranian schools are contradictory. “The children are not allowed to enter Iranian schools… (because) the refugees do not have permanent permission to stay in Iran,” the international monitoring group reported in May 1989. Three months later, however, the High Administrative Committee stated that “the government has decided that students in elementary and high classes will have a place in the camps, towns and villages which have schools….” The following summer, the UNHCR also reported, in an internal memo, that in principle, access to state school system is not barred.

Whatever the policy, practical hurdles — lack of places, transportation, or language skills — have kept most of the refugee children at home. According to the High Administrative Committee, many children had to drop out because of the difficulties following instruction in Persian, the compulsory medium of instruction in Iranian schools. Only those children excelling in their first year were allowed to continue.

Two refugees interviewed by Middle East Watch said there was no possibility of schooling, except what parents could provide themselves. “There were more than 2,000 children in my camp near Urumia,” says a 31-year-old man. “No more than five or six of them were allowed to attend the local school.” Their parents had been in the camp since 1975 and received official favor. He taught his son and some neighboring children at home.

With a little outside help, many of the refugee groups could have established a system of their own. In one camp of 300 families, 51 adults had a professional degree, according to one visiting humanitarian group. It is not clear if Iranian officials allow such self-help efforts.

VI: Detention and Deportation

Most of the camps are closely guarded, and many have their own jail.67

Refugees claim that camp authorities often used the jail to enforce religious observance or to squelch complaints. One refugee said that in his camp, a settlement of more than 10,000 people near the city of Urumia, the pasdaran (Revolutionary Guards) locked up people who tried to escape or refused to pray. Hewa, another refugee, spent several days in the lock-up for refusing to pray and complaining about the food. Another member of that camp spent two months in the jail for organizing a hunger strike to demand a permit to leave the camp.

On the other hand, says one former inmate, the jail was not an intimidating punishment, even though it had no windows or beds. “There is no difference between theqalantina (jail) and the rest of the camp,” he explained.68

Medico International, a foreign relief agency, also reported after a visit late in 1989:

The refugees are frequent victims of arbitrary action by the Revolutionary Guards who control the area and the camps by means of numerous road-blocks… Iraqi Kurds report arbitary arrests and confiscation of papers by the pasdaran.69

No less eager than Turkey to pass the burden onto other countries, Iran’s policy over repatriation of the Kurdish refugees has been mixed. One Kurdish exile says the police jailed several refugees from his camp who wanted to take advantage of one of the Iraqi amnesties. Another Kurd, however, wrote a relative that the government tried to forcibly repatriate those who complained about their treatment in Iran.70 The policy may have changed after Iran and Iraq signed their ceasefire accord in August 1988.

According to one refugee who managed to escape to the West, Iran became more aggressive by the end of 1989 about getting rid of the refugees. Those who had political problems in Iraq, he said, would be permitted to go to Tehran to try to arrange a way out of the country. “They would give you a laissez passer good for three months only.” At the end of the three months, the person concerned had to leave Iran on his own or be forcibly returned to Iraq. This young man personally saw three buses, with about 45 passengers on each, taking people back to Iraq. Friends in Iraq reported to him that at least 25 of the returnees had been executed.

Those who do not have political ties are also being pushed out, apparently willy-nilly. “They said if you have money, you have to leave for Europe; if you don’t have money, you have to move to Turkey or Pakistan,” said one refugee.71 This man saw Iranian guards load refugees onto buses headed for Turkey and Pakistan three times at the end of 1989 and beginning of 1990. It was not clear what choice the weary refugees had been given, either about moving on or their next destination.

VII: The Iraqi Kurds’ Status

Unlike Turkey, Iran has signed the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees and its 1967 protocols without geographical reservation, in theory giving the Iraqi Kurds all the protections discussed above. It is hard to assess Iran’s compliance, given the limited amount of information on the refugees, but there are indications that Iran has not abided by all the Convention terms.72

Non-discrimination is a basic principle underlying the convention. In granting rights or providing benefits, one group of aliens must not be treated more favorably than another. This applies to the right to work (articles 17 and 18), the right of association (article 15), access to housing (article 21) and freedom of movement (26). In other respects — access to courts, freedom of religion, public education and government assistance — the refugees are entitled to rights on a par with Iranian citizens.

As with Turkey, Iran has also short-changed the Kurds relative to other refugees. According to a 1988 UNHCR fact sheet, of the more than two million Afghan citizens who have sought refuge in Iran over the past decade, only three percent live in refugee camps:

This is the result of Government policy which has from the onset enabled refugees to settle in various provinces all over the country, take up employment and benefit from subsidized food rations, free education and medical care on the same terms as nationals. As a result, Afghan refugees are a familiar sight in almost every major city in central and eastern Iran, where they provide an important source of unskilled labour.73

While many Afghans have found a better life in Iran than back home, most of the Iraqi Kurds are still living in camps, restricted from travelling, settling elsewhere and, for the most part, finding work.

Breaking Out On Their Own

A few thousand refugees have tried to take matters into their own hands. With the help of friends or families, using smugglers or fake papers, over the past two years hundreds have fled from Iran or Turkey, sometimes to find themselves in an even more precarious situation.

The largest group have made their way to Greece through neighboring Turkey. According to a KDP press release in December 1990, the Greek government had jailed 150 Kurdish refugee families seeking political asylum. Though Greece has signed the refugee convention, its position is that the convention does not make these people official refugees in Greece, since they had already found safe haven in Iran or Turkey. This stance is debatable given the treatment previously encountered by the Iraqi Kurds in their first countries of refuge.

Azad (a pseudonym), a naturalized American citizen, has a younger brother, Youssef (also a pseudonym), among those Iraqi Kurds who are still in Greek jails. Youssef has been in prison about eight months for a 13-month conviction for illegal entry into the country. It is not his first imprisonment. Ten years ago, he was arrested in Iraq and allegedly poisoned in jail. The brother implied that the arrest in Iraq was politically motivated.

Youssef then joined the peshmerga, only to flee to Iran after the chemical bombings in 1988. From there, he tried to escape to Pakistan, in punishment for which Iranian authorities jailed him for a month. A second escape attempt got him to Turkey and then to Greece. According to Azad, Greek authorities are now trying to return him to Iraq against his will — a clear case of refoulement.

Azad is trying to get Youssef to the United States. In an initial setback, however, a U.S. immigration official said the case was hopeless without more documentation of his identity and detention in Iraq. “It is illegal to send documents through the mail from Iraq,” laments the brother, not even mentioning the war and the danger such an effort might pose to their parents and siblings still in Iraq.74

Another 1,500 to 2,000 of the Iraqi refugees have moved east, to Pakistan, where the government has also jailed many of them for illegal entry. Here, at least, the UNHCR has been able to get most released within a few weeks, according to Thomas Thompson, assistant chief of mission for Pakistan.75 Until then, however, the refugees are compelled to share cells with common criminals.

Because Pakistan has not signed the Convention on Refugees, it considers the Iraqi Kurds illegal immigrants, giving them no possibility to “regularize their status,” as the UNHCR’s Thompson puts it — i.e. to be absorbed into Pakistani society. None have work permits and the thousand or so who arrived after May 1989 — an arbitrary date linked to the supposed improvement of refugee conditions inside Iran after the death of Iran’s leader Ayatollah Khomeini — are not allowed to travel outside Baluchistan province. Though enforcement of the travel restriction is much less efficient than in Iran or Turkey, most still have nothing to do and no reasonable prospects for a normal life in Pakistan.

Recommendations

In light of Iraq’s history of using chemical weapons on the Kurds, Middle East Watch urges the United States to:

-

demand that outside monitors be allowed to stay in Iraq to make sure it does not again use chemical gas during the post-war insurrection now reportedly taking place in the Kurdish provinces.

-

insist that Iraq’s violations of international laws against the Kurds — including its use of poison gas in 1987 and 1988 — be included in any war crimes trials against Iraqi leaders, should they take place.

-

continue the embargo of Iraq until it dismantles its forced resettlement program and allows its Kurdish citizens to return to the villages they left because of the chemical bombings.

-

demand that outside monitors, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, be allowed to assure that any Iraqi Kurds in exile may safely return to Iraq.

Because of Iraq’s treatment of the Kurds and the appalling conditions under which Kurdish refugees are living in Turkey, Iran, Greece and Pakistan, Middle East Watch also recommends:

-

that the United States and other Western countries give asylum to significantly greater numbers of Kurdish refugees;

-

that Greece and Pakistan stop jailing Iraqi Kurds for illegal entry, release those currently in prison and grant official refugee status to those who have sought asylum;

-

that Iran abide by the Convention on Refugees in its treatment of the Kurdish refugees, including the provisions related to schooling, employment, travel, residence and the administration of justice.

Notes

1 Official Iraqi and Turkish government figures, as cited in Amnesty International, Iraqi Kurds: At Risk of Forcible Repatriation (London: Amnesty, June 1990), pp. 2-3, 7. The actual number may be much higher.

2 According to leaders of the Diyarbakir refugee camp in southeastern Turkey, of the Kurds who have returned to Iraq from Turkey, 15 are known to have been executed and 350 imprisoned. Approximately 25 families, including 80 adults, are said to be imprisoned near Dohuk. Middle East Watch interview with Salih Haci Huseyin, Diyarbakir, Turkey, November 1990. See also Amnesty, At Risk of Forcible Repatriation.

3 The Latest Soviet census says that 153,000 people declared themselves to be Kurds. But Soviet Kurdish sources assert that due to assimilation, the real number could be as many as 500,000.

4 Turkish law bans speaking or writing in Kurdish — thus making broadcasts, publications, schooling and even singing in Kurdish illegal. So stringent is Turkey’s ban on the Kurdish language that the law outlawing it is crafted so that it, too, does not actually mention the word Kurdish. All Kurdish parties are also banned and writers, politicians and editors are frequently prosecuted for fomenting “separatist propaganda” if they write, even in Turkish, about the Kurdish question. At President Turgut Ozal’s request, Turkey’s parliament is considering a bill that would lift a few of the bans on speaking Kurdish — allowing Kurds to converse in their mother tongue at home or on the streets, and to sing Kurdish music — but even that limited move has met resistance from some Turkish parliamentarians who fear it could lead to renewed drives for Kurdish separatism.

5 A major point of contention was the government’s “Arabization” policy. According to the exiled Kurdish writer Ismet Sheriff Vanly, in September 1971, Iraq deported about 40,000 Faili Kurds to Iran. In 1973 and 1974, it forcibly evacuated several Kurdish villages and gave their lands to Arabs. In February, 1974, 400 Kurdish families had to leave the oil city of Kirkuk after the government replaced Kurdish workers with Arabs. Ismet Sheriff Vanly, “Kurdistan in Iraq,” People Without a Country (London: Zed Press, 1980) .

6 Peshmerga, the Kurdish name for their fighters, literally translated means “those who court death.”

7 According to Kurdish political sources, the mass relocation to Arab towns and villages in the south was another part of the government’s forced assimilation program. These sources say the government put many of those deported into detention camps and dispersed the rest among Arab communities, including Ramadi, Nasseriaeh and Dewianya.

8 The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, one of the main Iraqi Kurdish rebel groups, has documented 3,839 destroyed hamlets, villages and towns. See Shorsh Resool, Forever Kurdish: Destruction of a Nation (July, 1990).

9 Middle East Watch interview with Iraqi Kurdish exile, London, October 31, 1990.

10 Middle East Watch interview with Kurdish exile, London, October 31, 1990.

11 Stephen Pelletiere, Douglas Johnson and Lief Rosenberger, Iraqi Power and U.S. Security in the Middle East (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, 1990), p. 52.

12 Ibid., p. 90 n138. The note goes on to say that Iraq maintains it has never used the weapon “against civilians as part of a program of genocide.” It is not clear if that means it might have used it against civilians in a city under siege, as Halabja was at the time.

13 Throughout the war, Iran had supplied the Iraqi Kurdish rebels with safe haven and other support; Iraq was doing the same for the Iranian peshmerga, who had been waging a similar campaign for autonomy in their adjoining Kurdish region.

14 Middle East Watch, Human Rights in Iraq (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990), pp. 83-84.

15 Middle East Watch interview in U.S. (location and family name concealed to protect source); September 5, 1990.

16 Middle East Watch interviews with exiles, London, October 1990, and Diyarbakir, Turkey, November 1990.

17 Peter Galbraith and Christopher Van Hollen, Jr., Chemical Weapons Use In Kurdistan: Iraq’s Final Offensive — a Staff Report to the Committee On Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, Oct. 1988).

The authors interviewed more than 200 Kurdish refugees who fled to Turkey. See also Middle East Watch, Human Rights in Iraq, pp. 75-85 and Physicians for Human Rights, Winds of Death (Somerville, Massachusetts: PHR, February 1989). More recent interviews of survivors by Middle East Watch produced further corroboration, with similar details; interviews London, October 1990, Diyarbakir, Turkey, November 1990.

18 The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), one of the main Kurdish rebel groups, whose figures are usually conservative and reliable, puts the Kurdish death toll for the year at nearly 20,000. Other accounts have given figures several times higher.

19 Hazhir Teimourian, “Kurds Appeal for Help Against Chemical Weapons,” The Times, London.

20 Middle East Watch, Human Rights in Iraq, p. 78.

21 Some of Turkey’s tactics would be familiar to Iraqi Kurds. Like Iraq, Turkey has forcibly emptied scores of Kurdish villages, allegedly for security reasons. Ankara has also tried to force Kurds to take up arms against the guerrillas through a village guard system. Frequently, villagers who refuse to join this citizens’ militia are arrested and tortured at the local police station. When no one signs up, special forces have forcibly evacuated the entire settlement. (Information drawn from Middle East Watch interviews in Turkey, November 1990.)